29 Nov Preventing Harm with Firearm Policy: An Interview With TL1 Trainee Kelsey Conrick

The ITHS interview series is meant to shine a deserving spotlight on individuals who are doing critical but sometimes invisible work across the vast spectrum of translational science. In our third installment of this series, we spoke with Kelsey Conrick, a PhD student at the University of Washington School of Social Work, and member of the 2022-2023 TL1 Translational Research Training Program cohort at ITHS. Her focus is on firearm policies, and her dissertation seeks to develop resources to help equip social workers to prevent firearm-related harm to their clients. Currently, Conrick is interviewing social workers to better understand their need for resources in serving clients who are at risk of causing harm to themselves or others with a firearm. Conrick also has 15 peer-reviewed articles (five as first-author), as well as four that are currently under review.

We sat down with her to learn more about her academic journey and what she hopes to achieve. This interview has been edited and condensed.

How did you get involved in this work?

Conrick: I grew up in an extremely pro-gun culture and a pro-gun household. One of the main reasons why I was initially drawn to this work is because there are many different perspectives on ways to reduce the number of people who are killed or injured by firearms. I have always admired the work of Dr. Ali Rowhani-Rahbar and Dr. Fred Rivara who are leading experts in firearm injury. Reading their work and understanding the gravity of gun violence led me to a point where I felt called to help reduce that burden.

There is often disagreement on how we get to that goal, but the one universal agreement is to remove access to firearms from people who are at imminent risk to harm themselves or others with a firearm. And again, there are many ways to remove that firearm. We can remove firearms involuntarily, but many people have concerns about involuntary removal and violation of rights. These situations can quickly escalate, especially when marginalized community members and law enforcement are involved. My research involves figuring out ways to mitigate these types of situations by considering both voluntary and involuntary removal.

What is your goal with this work?

Conrick: My research question is about how social workers can support people who are in situations of either committing harm or potentially being harmed by firearms. These are people who have access to firearms and may die by suicide, cause harm to others, or those who are experiencing situations such as domestic violence.

I believe social workers have a unique perspective. They are trained to analyze a person’s risk factors of being harmed or doing harm as well as identify a person’s protective factors. They also have tools to support people through social justice and understand the broader context of people’s lives. When it comes to these types of potentially harmful situations, social workers will try to understand what is currently happening in this person’s life and figure out how to provide support in a comprehensive way.

Currently, social workers do not have access to readily available training to counsel clients about firearm safety and are not trained to engage in these types of counseling processes. Also, depending on geography, these conversations can look very different. My mentor, Dr. Megan Moore, has been instrumental in helping me understand how to develop these resources.

The goal of my dissertation is to develop materials that explain policies and identify mental health and other resources that can be used to prevent or mitigate situations involving firearm-related harm.

Why is this your focus?

Conrick: There is a lot of interest in the social work sector to have well-thought-out and researched resources that can help them support those who are likely to harm themselves or others with firearms. I am currently interviewing social workers to better understand the level of support that they need in relation to firearm safety.

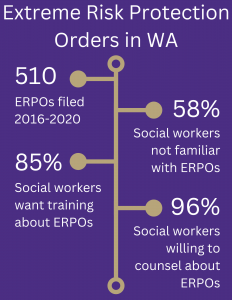

I recently did a presentation at the Washington State Society for Clinical Social Work. Through those conversations, I am learning that there is a lack of knowledge regarding the existence of policies around firearm safety. I am working on gathering information to build tools and resources that social workers can use daily.

Another focus of my dissertation is understanding gun responsibility/control policies such as Extreme Risk Protection Orders (ERPO). This policy allows a person, usually a family member, household member, or law enforcement, to file a petition to restrict access to guns based on evidence that someone poses gun-related threats. This process focuses on due process to make sure that basic rights are not being violated. It is designed to be a temporary order that goes through the civil system instead of the criminal system. Criminal records will not be filed unless the order is violated. ERPOs are relatively new laws and there are loopholes. Many social workers bring up moral and ethical conflict since ERPOs involve an involuntary removal process that involves the legal system. Many folks are understandably concerned about involving law enforcement with folks of color, the LGBTQ community, and with people who have mental health concerns. In cases like these, it can be helpful to support social workers to navigate the conversation to voluntary removal.

Gun control is a very polarizing topic in our society. How do you address those who have different viewpoints about guns?

Conrick: I always try to come at it from a place of curiosity rather than a place of judgment. I try to understand the type of thought process involved in coming to a pro-gun conclusion. My dad has always been my test subject to discuss this topic. He is pro-gun, but he is also a safe person for me to have these conversations. I have learned that approaching this subject from a place of curiosity makes the conversation flow much smoother. I will disagree with phrases such as that is not necessarily true and here are some facts that can help us understand this better.

I often hear the argument that even if firearms are removed by ERPOs in situations involving suicide attempts, a person can always find another way. That’s possible; however, firearms have a fatality rate of about 90%, so they are much more lethal than other means.

What do you do in situations where firearms have been a part of someone’s entire life, and suddenly, you are coming in and telling them that they can’t have their firearms anymore because they are a danger to themselves and others? Those conversations can be really hard.

You mentioned that you grew up in a very pro-gun culture. What was that like?

Conrick: Firearms were central to the culture for my family and the Alabama community I grew up. For example, I would have conversations with my dad about why it was necessary to have a Safety Team at church that had concealed weapons. The responses revolved around how God is calling them to be protectors of the church community, their chosen and biological family. The conversations led to answers such as how they were trained to respond to crises, and folks at church knew that if there was an emergency, the Safety Team would respond.

This led me to begin a study to better understand how people reconcile these types of Christian beliefs with firearm ownership and how these ideologies work together. I received a grant from the Harborview Injury Prevention & Research Center to begin this study and this study am very close to being published.

How did you get involved with the ITHS TL1 Translational Research Training Program?

Conrick: I was introduced to the TL1 program at ITHS by Vivian Lyons. She was a TL1 scholar during her PhD career, and there have been a couple of other people who had been TL1 trainees in my department. They all have very positive experiences and gained a lot from this program. This is what motivated me to apply. I had the opportunity to listen to inspiring people; one of my favorite seminars was led by Allison Coffin who talked about conversing about our work with people in both academia and outside of it.

What motivates you to continue this work?

Conrick: I’ve realized the things that drive my work have changed since I had my daughter. In the past, things I mentioned earlier such as finding out ways to decrease the burden of firearm injuries and deaths and finding a middle ground with those who have opposing views, motivated me. My daughter is nearly 5 months old, and though I won’t have to worry about school shootings for a while for her, there are parents who absolutely worry about that every single day.

Knowing that my work can potentially make a difference in firearm-related harm motivates me to continue this work.

Note from the Editor: Thank you so much to Kelsey Conrick for sitting down to talk with us about her professional journey. If you have a suggestion for a story or an interview profile, email Mihila Gomes to share your idea.